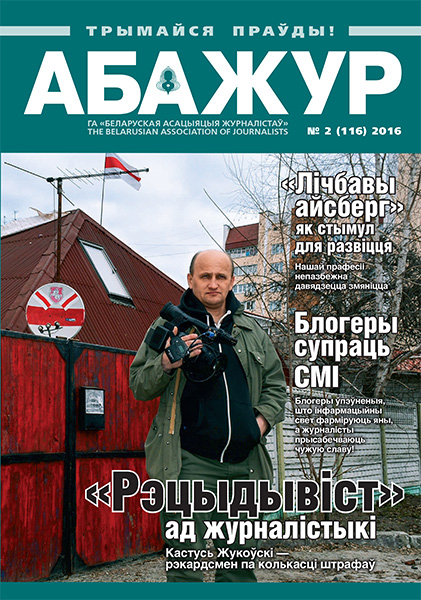

Recidivist from Journalism (interview from Abajour, abridged)

Kastus Zhukouski manages to do journalism, civil activism and defense of his own rights. Local law enforcement agencies take his name as a synonym to the word “opposition”. He is not going to reassure them, though.

His private house in the center of Homel turned out to be squeezed in between Soviet-time apartment blocks. There is a white-red-white flag waving above the house, and a placard of Uladzimir Niakliayeu, poet and politician, looking out from the window facing the town prison: the full-length portrait has been here since the presidential elections in 2010.

Many people deem Kastus extraordinary. His name became familiar to local public in 2007 when he actively investigated circumstances around a mass burial of victims of Stalinist repressions. At that time, the mass media were shaken by the information about the mass grave in the Shchakatouski forest, close to Chernihiv motorway. In short time, Kastus Zhukouski together with friends shot an amateur documentary “Stalin’s Line. Homel region”. Residents of nearby villages confirmed the version of civil activists about crimes of the NKVD (Soviet People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs). It seems that exactly at that moment, the excessively active citizen came in sight of local special services.

Then came a period of civil and political activities: Kastus was gathering signatures for oppositional candidates, staged anti-alcohol football tournaments, created a local web resource. In that time, he made a living from taxi driving and laying roofs. In between he helped local freelancers to make reports.

No way back

“I have no way back. Even if now I refused totally from confrontation with the authorities, who would believe me?” says ironically Kastus.

Colleagues remark the pugnacious temper of the cameraman. He boldly opens doors to officials’ cabinets, and covers those socio-economic topics that are silenced by the authorities. Which, of course, makes the local vertical grind the teeth.

The freelancer has got a good heritage from his former civil activities: numerous contacts with initiative people practically in the whole region of Homel. Often information from deep province demands travel: Kastus drives dozens, sometimes hundreds of kilometers to make a report. Taxi driver skills are of use.

We are sitting in a cozy kitchen with lots of history placards. The fridge is decorated with magnets of many civil campaigns that Kastus used to organize. Once, having returned from builders’ work in Moscow, he bought a half-burnt wooden house. Gradually, he transformed the ruins into a decent cottage. Kastus says he could earn his living from physical work which he does not eschew until now. However, life has unexpectedly engaged him with journalism.

“From childhood, I fought for justice. I could start fighting when I saw deceit. Then I studied to be a jurist counsellor. This seems to be the source of my activeness in journalism,” he says.

I touch upon his reputation of a civil activist that has stuck to him until now; and he agrees to a certain extent.

“It seems to me that in Belarus it is hard to draw a distinct line between independent journalism and civil activism. As it often happens, public outcry can help solve certain social issues that the authorities have ignored for years. With this implication, certainly, I am still a civil activist.”

He also calls himself an amateur: “You can see yourself as a specialist when you reach some high results in your sphere. I think that having desire, humanities education or pursuit of justice are not enough to call oneself a professional. Like, for instance, for drivers’ license, I have category B, so I am an amateur. And there are real professionals somewhere around!” – he laughs. “To be serious, there are several talented journalists in Homel, who do their job in a very professional and responsible manner, but they can be counted on fingers. I consider myself an amateur, a freelancer who shoots the real life, that is what I see.”

Reasons for persecution

Today Kastus Zhukouski has got the record number of administrative fines. He has been charged with “illegal production of informational products” without accreditation. The sum to be paid to the state exceeds 70 million Belarusian rubles.

The prosecution follows a beaten scheme designed by Belarusian law enforcement agencies. After a report is broadcast on the satellite channel Belsat, policemen interrogate heroes of the material, and they have to give explanations which serve as a basis for administrative process which ends up with a trial. The outcome is known beforehand. Paradoxically, serious arguments like obligations of Belarus in the sphere of freedom of speech within international agreements do not work here.

Kastus Zhukouski says that one can only guess what the real reasons are behind the persecution. But he thinks that his video reports – about closing industrial enterprises, about failures of social standards to be met by the state, about people’s poverty – all this ruins the myth of the so-called social state. The journalist also assumes that critical materials might “spoil reputation” of someone from the vertical, and what he is faced with is revenge.

“As for the policemen who all the time scour in my footsteps, I can say that in Homel, these comrades have long ago crumpled their conscience. I say it because I have to deal with them quite often. I have a feeling that their bosses are more important for them than the Constitution of the country. It seems that they deem conscience an unnecessary complex that they need to get rid of,” says the freelancer. /…/

In several administrative cases, with the help of lawyers of BAJ, Zhukouski has exhausted all national legal remedies, with the last instance being the Supreme Court of Belarus. But there is hardly a single case when people in judicial robes defended the journalist: for several years in a row, there has been the ban for work for journalists without accreditation. Which, evidently, contradicts to norms of the Constitution and discredits the state at the international level.

One of the administrative cases with a fine in the decision for Zhukouski has been registered with the UN Human Rights Committee. Soon, the Belarusian government will have to give explanations why the correspondent performing professional duties was equaled to a participant of an unsanctioned civil action. This was a picket of Yury Liashenka, an invalid in a wheelchair from Svetlahorsk. As usually, it ended with detention of the picketer and the journalists Kastus Zhukouski and Larysa Shchyrakova.

/…/

At the end, I asked Kastus if his desire to do journalism has not waned. For, it is a hard fate to feel pressure and prosecution from the authorities all the time .

“You know, all the detentions, trials, fines – they are only circumstances of work. There is no heroism on my behalf. It is the same as if a policeman would refuse from going on duty if there were a risk of being killed. I chose independent journalism, and I don’t think it’s an exploit. It’s a wind blowing in the face and you know that it will blow constantly with alternating force. You just have to do your work, and everything will be fine.”

@bajmedia

@bajmedia