Attacks on journalists, bloggers and media workers in Belarus, Russia and Ukraine: 2017–2019

The Justice for Journalists Foundation conduct monitoring of attacks and violations of media rights in Belarus, Ukraine, and Russia. Public association "Belarusian Association of Journalists" has prepared an analytical report on Belarus.

INTRODUCTION

This report forms part three of a cycle of research studies on attacks against media workers in the 12 post-Soviet countries over the period from 2017 through 2019. As used in this report, the term “media workers” refers to journalists, bloggers, camera operators, photojournalists, and other employees and managers of traditional and unregistered media. This section of the study is devoted to Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine.

The report does not cover attacks against professional and citizen journalists in Crimea; statistics on assaults in this region have yet to be incorporated into the Media Risk Map. Full information about this topic can be found in the report Chronology of pressing the freedom of speech in Crimea, put together by the Crimean Human Rights Group and the Human Rights Centre ZMINA and published on February 9, 2020.

Assaults on media workers in the three Slavic states are being examined in a single report not only because of the geographic proximity and cultural similarity of these countries, but also to make it more convenient to compare the methods of suppressing freedom of speech that prevail in them.

METHODOLOGY

The data for the study have been obtained from open sources in the English, Belarusian, Russian, and Ukrainian languages using the method of content analysis. Lists of the main sources are presented in Annexes 2–7.

Based on further analysis of 3,063 incidents of assaults on professional and citizen journalists, bloggers, and other media workers, as well as on the editorial offices of traditional and online publications, three basic types of attacks have been identified:

-

Physical attacks and threats to life, liberty, and health

-

Non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats

-

Attacks via judicial and/or economic means

Each of the types of attacks presented is further divided into sub-categories, a complete list of which is presented in Annex 1.

PRINCIPAL TRENDS

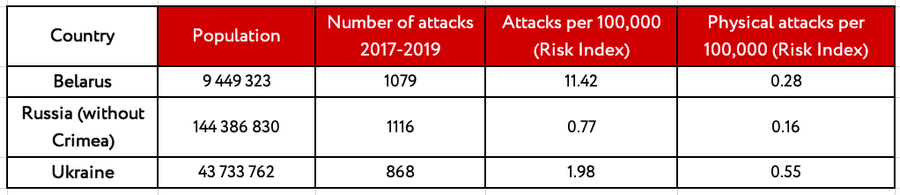

The total combined population of Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine numbers nearly 200 million people, which corresponds to approximately 45% of the population of the European Union. For a proper analysis of the risks of assaults on media workers, it would be advisable to look at not the absolute numbers of attacks, but at the relative figures: per 100 thousand people. According to calculations, journalists from Belarus are subject to the greatest risk of assault, although the risk of physical assault is higher in Ukraine.

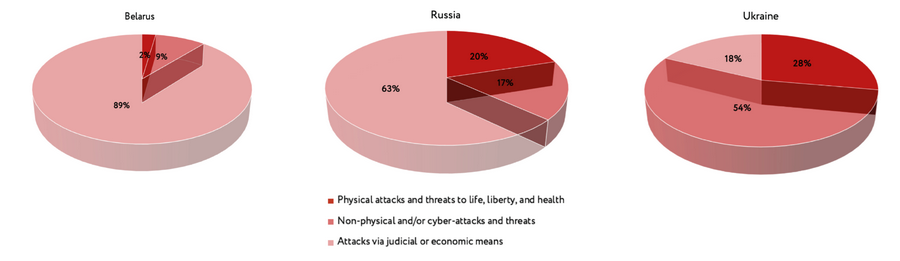

Belarus holds second place after Armenia among the 12 post-Soviet countries in terms of the relative number of attacks against media workers per 100 thousand people, with a risk index of 11.4. The principal method of assaults on journalists in Belarus are attacks via judicial and/or economic means – these comprise 89% of the total. The principal source of danger for media workers are the authorities – above all the police and the courts. A “package” form of attacks predominates in Belarus, in the course of which a media worker is detained short-term, tried, and arrested for 72 hours and sentenced to payment of a fine. The most frequent “administrative offence” is cooperation by Belarusian freelance journalists with foreign media without Foreign Ministry accreditation. Sometimes searches of a journalist’s work premises and residence with confiscation of equipment and documents form a component part of such a “package attack”.

Russia, along with Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan, exhibits indicators of relative risk of being subjected to assault that are not high for post-Soviet countries – 0.77. However, for Moscow, with a population of 12.5 million persons, this risk comprises a considerably higher 2.95. It may be assumed that such numbers can be explained by the peculiarities of monitoring assaults in this country. Russia stands out with its high number of deaths among media workers: 15 people perished as the result of murders, accidents, beatings, and suicides, a number twice as high as in all 11 post-Soviet countries taken together. The most widespread type of assaults on media workers in the country are attacks via judicial and economic means. The number of recorded short-term detentions of journalists by police in the period covered in this study exceeded 200 incidents, while 40 journalists were sentenced to various terms of deprivation of liberty.

In Ukraine, the relative index of attacks against journalists comprises nearly 2 per 100 thousand people, which puts the country in sixth place among the 12 post-Soviet countries in terms of degree of risk for media workers, between Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan. It should be noted that in zones of combat activities – Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts – 43 assaults on journalists have been recorded, while in Kiev Oblast the number is 385. Nearly 28% of all recorded assaults on media workers in Ukraine consist of attacks of a physical nature (beatings, abductions, attempted murders). Moreover, in more than half of the cases, those committing the assaults were not connected with the authorities. In this country, the prevailing methods for pressuring journalists are bullying and intimidation, including in cyberspace, as well as damaging and seizure of property and documents. The decline in the overall number of attacks from 357 in 2017 to 245 in 2019 gives cause for optimism.

RISK REDUCTION MECHANISMS

Analysis of the risks for media workers, as well as of their geography, frequency, and sources, is a necessary precondition for working out methods of protection and safeguards. Even taking into account the limitations associated with the ability to track assaults on media workers, analysis of the data obtained allows us to offer several recommendations for more effectively withstanding attacks in each of these countries.

-

In Belarus, the source of the attacks on journalists in the overwhelming majority of cases is the authorities, while the function of the courts usually comes down to rubber-stamping a repressive decision that has already been adopted. That said, there is a rather effective system of monitoring attacks in place in Belarus, a country where the president has been in office for more than 26 years already and independent media inside the country have been practically annihilated while Belarusian journalists are subjected to harsh administrative and even criminal prosecution for cooperation with foreign publications.

In these conditions, public disclosure of incidents of assaults on journalists, drawing public attention, payment of fines, and in the event of repeated targeted attacks, leaving the country and continuing to work abroad, present themselves as the most effective methods of protection.

-

In Russia, the risks for media workers are increasing with each passing year and come above all from the authorities, who regularly deprive professional and citizen journalists of liberty and beat them up. Besides that, the adoption of ever more repressive laws is expanding the arsenal of methods of “judicial” influence on independent media, compelling an ever greater number of journalists to leave the profession. In the meantime, the number of fatal incidents, attempted murders, beatings, and torture of journalists growing, while the investigations of these incidents remain at an unsatisfactory level.

Recording the various types of attacks on independent publications and journalists has important significance for a more precise assessment of the risks. Drawing public attention to violations of the rights of media workers remains the most effective method of protecting Russia’s journalists. Besides that, it is extremely important to provide them with timely and professional legal assistance. Inasmuch as one fifth of all attacks are connected with beatings of journalists, training courses on physical security would allow for a reduction in the risk of physical assaults.

-

In Ukraine, the overall number of attacks on journalists is dropping, but the risk of physical assaults nonetheless remains high. Monitoring of threats and non-physical attacks is efficiently organised in this country, which is instrumental in intensifying vigilance on the part of journalists. It is perhaps on account of this that it is proving possible to prevent some portion of the more egregious crimes. That said, the work of the courts in investigating crimes against journalists and finding and punishing the perpetrators does not seem to be effective.

In such conditions, the work of improving the monitoring of assaults ought to be continued, as should the informing of broad strata of society about the situation and the adoption of the necessary measures of protection, including protection by the state. Besides that, training courses on physical and cyber security for journalists have proven useful.

The Justice for Journalists Foundation, together with its partners and experts, carries out weekly monitoring of attacks against media workers in all post-Soviet countries excluding the Baltic states, the results of which are published on the Media Risk Map in both Russian and English. The available data covers the period from 2017 onwards.

BELARUS

1/ MAIN CONCLUSIONS

1,079 incidents of attacks/threats in relation to professional and citizen media workers and editorial offices of traditional and online publications in Belarus were identified and analysed in the course of the study. The data were obtained from open sources in the Russian, Belarusian, and English languages using the method of content analysis. A list of the main sources is presented in Annex 2.

-

Attacks via judicial and/or economic means are the most widespread form of pressure on journalists, bloggers, and media workers in Belarus. 957 incidents in this category were recorded.

-

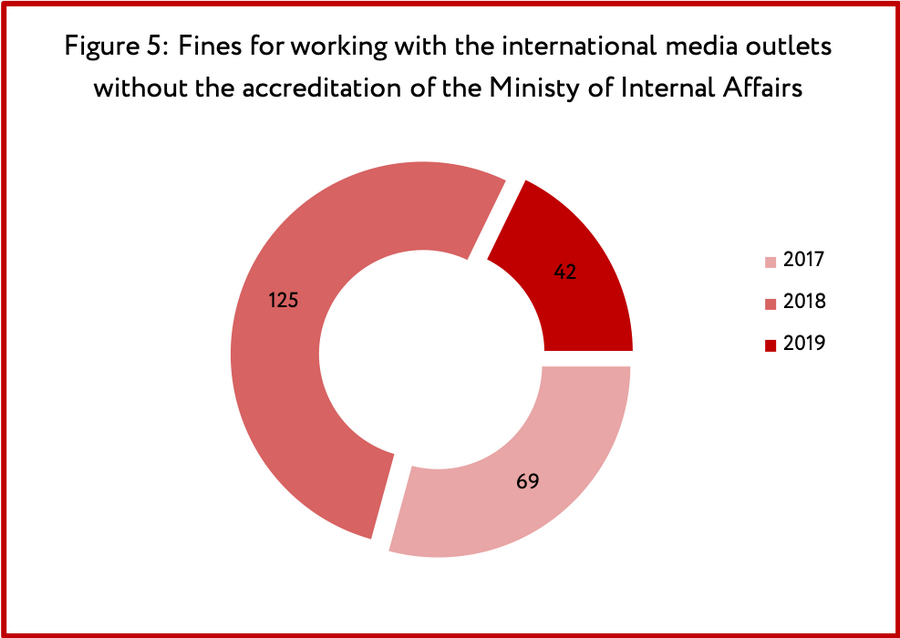

The most prevalent method of attack via judicial and/or economic means is fines for cooperation with foreign media without Foreign Ministry accreditation. The number of incidents in this sub-category is 236.

-

The number of physical attacks in Belarus is very low in comparison with other countries in the post-Soviet space. 26 attacks in this category were recorded over the period covered in this study.

-

The BelTA case is the most high-profile criminal case to be brought against a media workers in Belarus in the years 2017–2019.

-

Most often it was freelance journalists working for the satellite television channel Belsat who were subjected to attacks – in 623 of the 1,079 recorded cases.

2/ THE MASS MEDIA IN BELARUS. THE BRIEF OVERVIEW.

Registration of print media in Belarus, just like television and radio broadcasters, is mandatory and by license, and is exercised by the Ministry of Information. According to data provided by the agency, 1,614 print media outlets were registered in Belarus as of January 1, 2020. Of these, 435 print publications are state-owned, which allows the Belarusian authorities to state that private media predominate in the country. However, the vast majority of non-state-owned print media are strictly entertainment and advertising. According to the data of the Belarusian Association of Journalists (BAJ), there are no more than 30 registered non-state-owned media outlets of a socio-political nature. Nearly half of these were removed from the state’s newspaper subscription and retail distribution networks as far back as 2005, and only in 2017 were they put back on the distribution lists of the state monopoly distribution enterprises (approximately 15 publications had ceased publication by this time).

At the same time, state-owned media receive not only administrative support and various kinds of preferences, but also public funding given out on a non-competitive basis. In 2019, the sum of such funding exceeded 72 million US dollars. The bulk of these funds (over 50 million dollars) were earmarked for the funding of the Belteleradiocompany [the state-owned broadcaster].

The situation with television and radio broadcasting in Belarus meets democratic standards even less. Of the 270 registered television and radio programmes, the overwhelming majority (188) belong to the state. The remaining 82 non-state-owned television and radio stations are under the complete control of the authorities, both local and national, by virtue of the registration and licensing system.

Foreign stations disrupt the state’s monopoly on broadcasting. Radio Liberty, European Radio for Belarus, Radio Racyja, and the satellite television channel Belsat play a particular role (the latter three media outlets listed are registered in Poland). Their programmes are aimed at Belarusians and are prepared primarily by Belarusians. However, neither Belsatnor Radio Racyja have legal status in Belarus, despite efforts to open news offices and obtain accreditation for their journalists. Freelancers working with them come under constant pressure on the part of the authorities. Since 2014, they are being fined for “violation of the order for production and distribution of media output” (Article 22.9 of the Code of Administrative Offences). Based on police reports, in the years 2017–2019 freelance journalists were fined 231 times for working with foreign media without accreditation, for an overall sum equivalent to nearly 100 thousand US dollars. For reference, the average monthly salary in Belarus is around 500 dollars.

The internet remains the freest information space in Belarus. According to data from a study conducted by the Informational-and-Analytical Centre under the president’s administration, in 2017–2018 around 60 percent of respondents were receiving their news from the internet (72% from television), while among young people this percentage was significantly higher. Moreover, the majority of the ten most popular internet sites is made up of non-state-owned sites.

The Belarusian authorities reacted to the growing significance of the Internet by tightening control over it. At the end of 2017 and the start of 2018, by decision of the Ministry of Information, two popular news sites in Belarus were blocked: Belorussky partizan [Belarusian Partisan] and Khartiya 97 [Charter 97]. In 2018, criminal cases were opened against key players in this sphere (most notably the “BelTA case”; see Section 5 “Attacks via judicial and/or economic means”), and several popular regional bloggers came under pressure (in the form of criminal cases, administrative prosecution, and threats). Changes were introduced to legislation to tighten state regulation of the Belarusian segment of the World Wide Web. In particular, identification of users of internet sites was made mandatory, pre-moderation of comments was effectively introduced, and the culpability of website owners was increased. The new law allows for the voluntary registration of internet sites as media outlets (online publications), but this registration procedure has remained costly and complicated. Despite the fact that internet sites not registered as online publications are not now considered media outlets, and their journalists cannot enjoy the corresponding status, only 6 non-state-owned sites had gone through registration at the Ministry of Information as of January 1, 2020 due to the complexity of the registration requirements and the unclear benefits to be gained from this registration in the current circumstances.

In the annual World Press Freedom Index of Reporters Without Borders for 2020, Belarus ranks 153rd out of 180 countries.

3/ GENERAL ANALYSIS OF ATTACKS

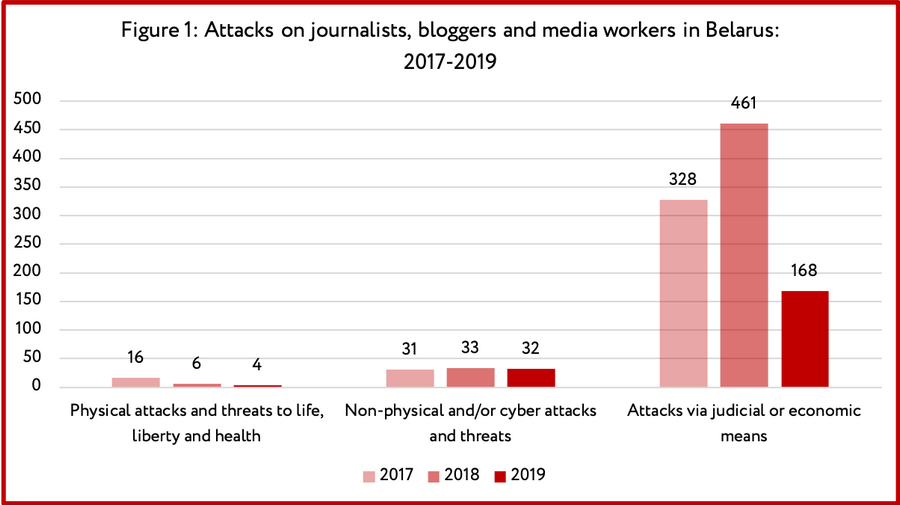

Figure 1 presents a quantitative analysis of the three main types of attack perpetrated against journalists in Belarus in the period from 2017 to 2019. The principal type of attack against journalists, bloggers, and media workers were attacks via judicial and/or economic means. These comprised 88% of the overall number of attacks captured in this study: 957 out of 1079.

The number of attacks of this type correlated with the change in the country’s political and economic situation. The increase in protest sentiments and mass demonstrations in Belarus also gave rise to intensified pressure on the media, journalists, and bloggers covering them. Thus, the peak of short-term detentions of journalist (93 people) in the period covered in this study occurred in 2017, when mass demonstrations against an unpopular presidential decree regarding the establishment of a special tax for unemployed people took place in all of the regions of the country.

During the period covered in this study, it was most often journalists from the satellite television channel Belsat who were the target of attacks – 623 out of the 1,079 recorded incidents. A number of journalists from the television channel experienced systematic pressure on the part of the authorities: Konstantin Zhukovsky (76), Olha Chaychits (59), Andrey Kozel (40), Alexandr Levchuk (36), Andrey Tolchin (34), Ekaterina Andreyeva (33), Dmitry Lupach (32), Milana Kharitonova (31), Larisa Shchiryakova (29), Sergey Kovalev (22), Lyubov Buryanova (Luneva) (19), Sergey Kvarchuk (16), Irina Orekhovskaya (13), Alina Skrabunova (12), and Alexandr Borozenko (11).

4/ PHYSICAL ATTACKS AND THREATS TO LIFE, LIBERTY, AND HEALTH

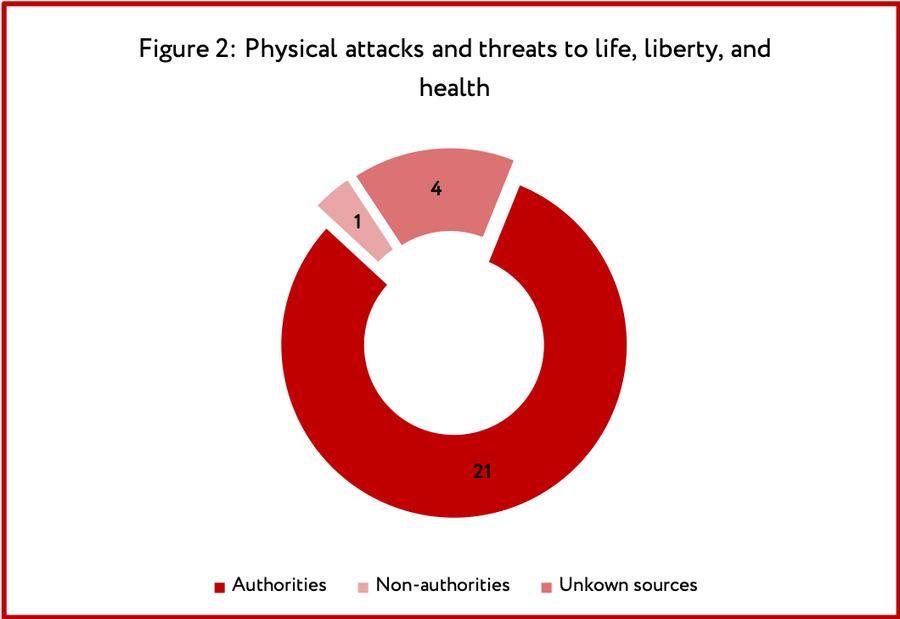

he number of physical attacks on journalists in the period covered in this study was comparatively low at 26. As has already been noted, the majority of them (16) occurred during 2017, when mass protest actions were taking place in Belarus.

Most often, the journalists were subjected to violence during short-term detention or obstruction of their professional activity. Appearing as the main aggressors were representatives of the authorities (in 84% of the incidents), first and foremost police personnel. Thus, in Minsk on March 25, 2017, during the traditional Freedom Day opposition demonstration, 5 journalists were beaten up by security personnel, including a British journalist covering the protest action.

Most often, the victims of physical attacks became journalists working with the Belsat television channel – 15 of the 25 cases. Subjected to physical pressure five times during the period covered in this study was Konstantin Zhukovsky, a journalist from Gomel, who holds the record for the number of fines issued to him:

-

In July 2017, Zhukovsky was detained short-term by employees of the traffic police (the state automobile inspectorate) when he was returning from a court where he had been covering the proceedings. The journalist was handcuffed to a tree.

-

In August 2017, during a video shoot, he was sprayed in the face with an aerosol substance by a person who turned out to be a management employee of a local pig farm. Zhukovsky was hospitalised.

-

In July 2018, the journalist suffered a hypertensive crisis after being detained short-term on a charge of petty hooliganism and taken to the local police station and then to court.

-

In November 2018, the journalist was summoned to the military draft commissariat for a medical examination. He had already undergone a medical examination less than six months earlier but never had been subsequently called up for training.

-

In January 2019, Zhukovsky was, in his words, assaulted by unidentified persons on a road in Gomel Oblast.

At the end of January 2019, Zhukovsky fled Belarus and requested political asylum in one of the countries of Western Europe.

In February 2018, the journalist Andrei Kozel, who likewise worked with the Belsat television channel and had been charged with administrative offenses on numerous occasions, was beaten up for attempting to film the vote-counting at a polling station. The journalist was brutally detained short-term and placed in detention, where he continued to get beaten up, and was subsequently charged with an administrative offence, allegedly for resisting employees of the police.

At the start of 2020, Kozel was forced to leave Belarus due to the constant pressure.

5/ NON-PHYSICAL AND/OR CYBER-ATTACKS AND THREATS

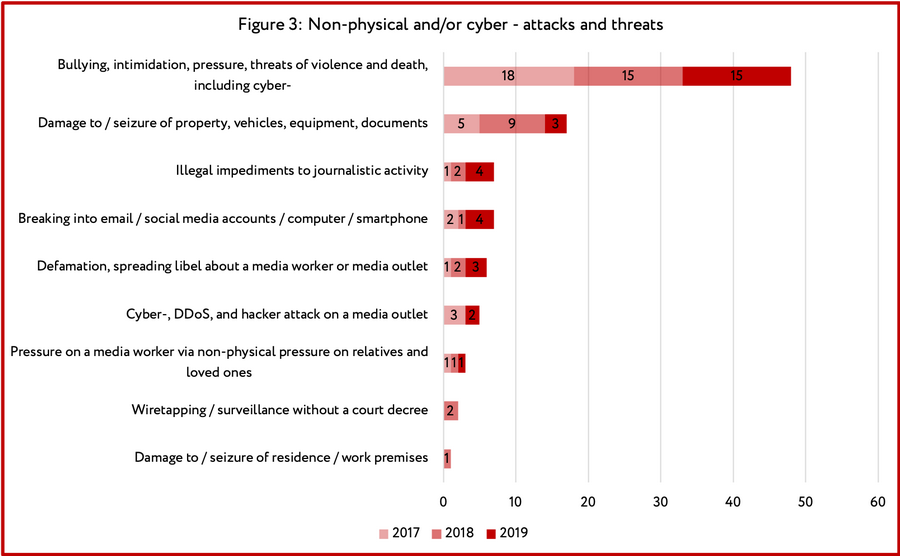

The most prevalent kinds of non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats over the period covered in this study were bullying, intimidation, pressure, and threats of violence and death, including in cyberspace. They comprised more than half (48) of the total number of recorded cases (95). The second most prevalent method of non-physical pressure is damage to or seizure of property, vehicles, equipment, or documents (16). Journalists encountered the highest number of attacks of this type (9) in 2018.

In Belarus, as in Russia and the countries of Central Asia, one of the most prevalent methods of attack is pressure on a media worker by way of non-physical pressure on relatives and loved ones:

-

In October 2017, the parents of Belsat journalist Alexandr Zalevsky were threatened over the phone by a stranger who identified himself as a KGB lieutenant.

-

In February 2018, a search was carried out at the flat of YouTube blogger Stepan Putilo’s parents. Security personnel seized a notebook computer and a video camera. Putilo, who was studying in Poland at that moment, was inculpated under Article 368 of the Criminal Code (insulting the president).

-

In September 2019, Petr Kuznetsov, founder of Homel website Silnye Novosti [Strong News], complained that he personally and his relatives and acquaintances are constantly having problems when crossing the border.

In a number of situations, representatives of the authorities threaten journalists with taking children from the family:

-

In July 2017, representatives of the authorities threatened Belsat journalists Olha Chaychits and Andrey Kozel that they would file a complaint with child protection services regarding their children.

-

In April 2017, they threatened to register the family of Belsat journalist Larisa Shchiryakova as indigent and to remove the child from the family.

Cyber-attacks are a less prevalent method. During the period covered in this study, 5 cases of hacking and DDoS attacks and 7 incidents associated with breaking into social media accounts were recorded.

6/ ATTACKS VIA JUDICIAL AND/OR ECONOMIC MEANS

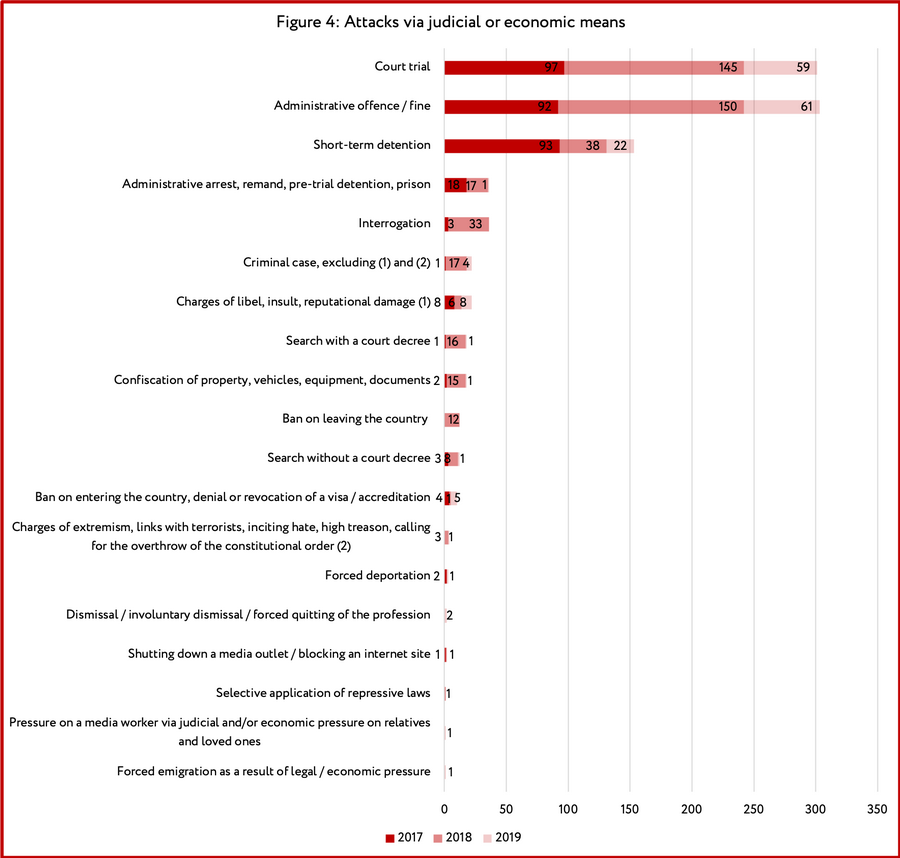

Figure 4 presents a general analysis of attacks via judicial and/or economic means. 957 attacks in this category were recorded during the period from 2017 through 2019. The top 3 methods of pressure include: administrative offences and fines; courts and court trials; and short-term detentions. In 942 out of the 957 recorded attacks in this category (i.e. 98% of the incidents), appearing as the “aggressors” were representatives of the authorities.

The most frequent reason for the attacks was the cooperation of Belarusian freelance journalists with foreign media without Foreign Ministry accreditation. Based on police reports, the courts fined journalists in accordance with Part 2 of Article 22.9 of the Code of Administrative Offences, which prescribes culpability for the illegal production and/or distribution of media output. 2018 became the “peak” year, when journalists were held administratively liable under this article no fewer than 122 times (more than in the previous four years combined). The overall sum of the fines for the year exceeded 43 thousand euros.

In most of the cases, the fines were issued to journalists working with the Belsat satellite television channel. Belsat is a part of the structure of Polish Television but positions itself as Belarus’s first independent television channel. All told, journalists and employees of the Belsat television channel were subjected to attacks via judicial and/or economic means a total of 574 times during the period covered in this study.

In March 2017 and April 2019, searches with confiscation of equipment were carried out under various pretexts in the Belsat television channel’s unregistered Minsk news office. One of the pretexts was an accusation of unauthorised use by Belsat of its name (there is a commercial enterprise of the same name operating in Belarus). Journalists were asserting that after the seizure of the equipment, police employees were affixing a Belsat sticker on their gear, which later served as grounds for its confiscation on the pretext of trademark infringement.

Criminal prosecution of journalists, media editors, and bloggers (and the searches, interrogations, and arrests associated with this) was the harshest method of pressure. Moreover, in a number of instances, the criminal cases were not formally associated with freedom of expression. The “Regnum case”, “BelTA case”, and the criminal case against head of independent news agency BelaPAN Alexandr Lipai caused the biggest public outcry.

-

The “Regnum case”: In February 2018, the Minsk City Court issued a guilty verdict in a criminal case against three Belarusian authors who had been published in Russian media: Yury Pavlovets, Dmitry Alimkin, and Sergey Shiptenko. The court found them guilty of deliberate acts aimed at inciting hate between nationalities committed by a group of individuals, and sentenced them to five years of deprivation of liberty, with the serving of the sentence delayed by three years. The convicted parties were released in the courtroom. If they do not commit violations of public order and will be carrying out the court’s directives during the three-year delayed-sentence period, the court may release them from serving their sentences. The pretext for initiating the “Regnum case” became a Ministry of Information appeal to the Investigative Committee regarding features of extremism allegedly discovered in these authors’ publications. The defendants were held in custody for 14 months – from the moment of their short-term detention in December 2016.

-

The criminal case against Alexandr (Ales) Lipai: In June 2018, a criminal case was opened in relation to Alexandr Lipai, head of leading Belarusian independent news agency BelaPAN, in connection with wilful income tax evasion in a particularly large amount in the years 2016–2017. A search was conducted of Lipai’s flat; documents and professional equipment were seized. Belarusian human rights organisations claimed that there was a political undercurrent to the case and associated it with a general tendency of increasing pressure on non-state-owned media and Internet sites in Belarus. On August 23, 2018, Ales Lipai died of cancer at the age of 52. The criminal case against him was dropped following his death.

-

The “BelTA case”: In August 2018, raids were carried out at the editorial offices of the BelaPAN news company, the By web portal, and several other media outlets, as well as in the flats of a number of their employees. Around 20 journalists were detained short-term and interrogated by investigators. 8 were sent to a pre-trial temporary detention “isolator” for a term of up to 72 hours. Serving as the reason for the large-scale “special op” was the unsanctioned use by some journalists of passwords to the subscription feed of the government agency BelTA’s website. It should be noted that the BelTA website materials are openly accessible free of charge and were posted by the media outlets that were now under pressure in consideration of all the rules established by BelTA. Nevertheless, criminal cases on unsanctioned access to computer information entailing the causing of significant harm were initiated in relation to 15 journalists. At the end of 2018, criminal cases in relation to 14 journalists were dropped and they were cited for administrative violations in the form of huge fines and compulsory payment of indemnification to state-owned media outlets – BelTA and the presidential administration’s newspaper SB. Belarus segodnya. The only defendant to be held criminally liable became Marina Zolotova, editor-in-chief of the internet portal Tut.By. Notably, she was charged under a different article – failure to act by an official. In March 2019, the court found Zolotova guilty and sentenced her to a fine of 7,650 Belarusian roubles (more than 3,000 euros at the National Bank exchange rate).

Among the most serious internet-related violations, the blocking of popular internet sites that cover socio-political topics ought to be pointed out. There were two such blockings, and both became high-profile. Both internet sites were accused of distributing prohibited information (including on the conducting of unsanctioned mass demonstrations). But not only were they not issued any warnings that they were breaking the law or demands to remove specific materials, they did not even know what materials specifically had served as the grounds for their being blocked in Belarus. The websites continue their activity following a change of their domain extensions:

-

In December 2017, the Ministry of Information adopted a decision on restricting access to the Belorussky partizan website, the founder of which was the well-known journalist Pavel Sheremet, who had been working in Ukraine in recent years and tragically died there in 2016.

-

In January 2018, access was restricted to another popular website, Khartiya 97, whose editorial staff has been working in Poland in recent years (after the criminal prosecution of editor-in-chief Natalia Radina and a number of website employees on charges of organising mass disorders following the 2010 presidential elections).

Overview of attacks on journalists in Ukraine and Russia HERE.

@bajmedia

@bajmedia